Making art films has become more and more difficult and, therefore, daring and adventurous. Why more difficult? Because – over the last decades and increasingly so – we have been truly absorbing films and moving images almost daily. We have been learning to see the world through the lenses of cameras and are much more aware both of the space film can produce and of what to expect there. Also, we have grown used to the voices that are often superposed onto images by artists and film makers. Somehow, these voices become like surrogates of ourselves reading a text, making the effort of a commitment that goes beyond the action of just watching. We have also witnessed a proliferation of mainstream films using similar tactics and methods to art films and video art. All in all, we have become a better audience, and yet one increasingly difficult to surprise. Something else happened as well. We have become impatient: we do not enjoy long durée that much and find it more and more difficult to soak in a substance, preferring to jump from one thing to the next. Social media, alongside many other factors, conditioned us to anticipate shorter and “sparking” content.

I just wanted to share these remarks to be able to adequately address the adventurousness of the work of Pauline Julier. An adventurousness that consists in taking all these factors into account and turning each problem– one by one – into a new possibility for the genre and also for the causes her films thematize.

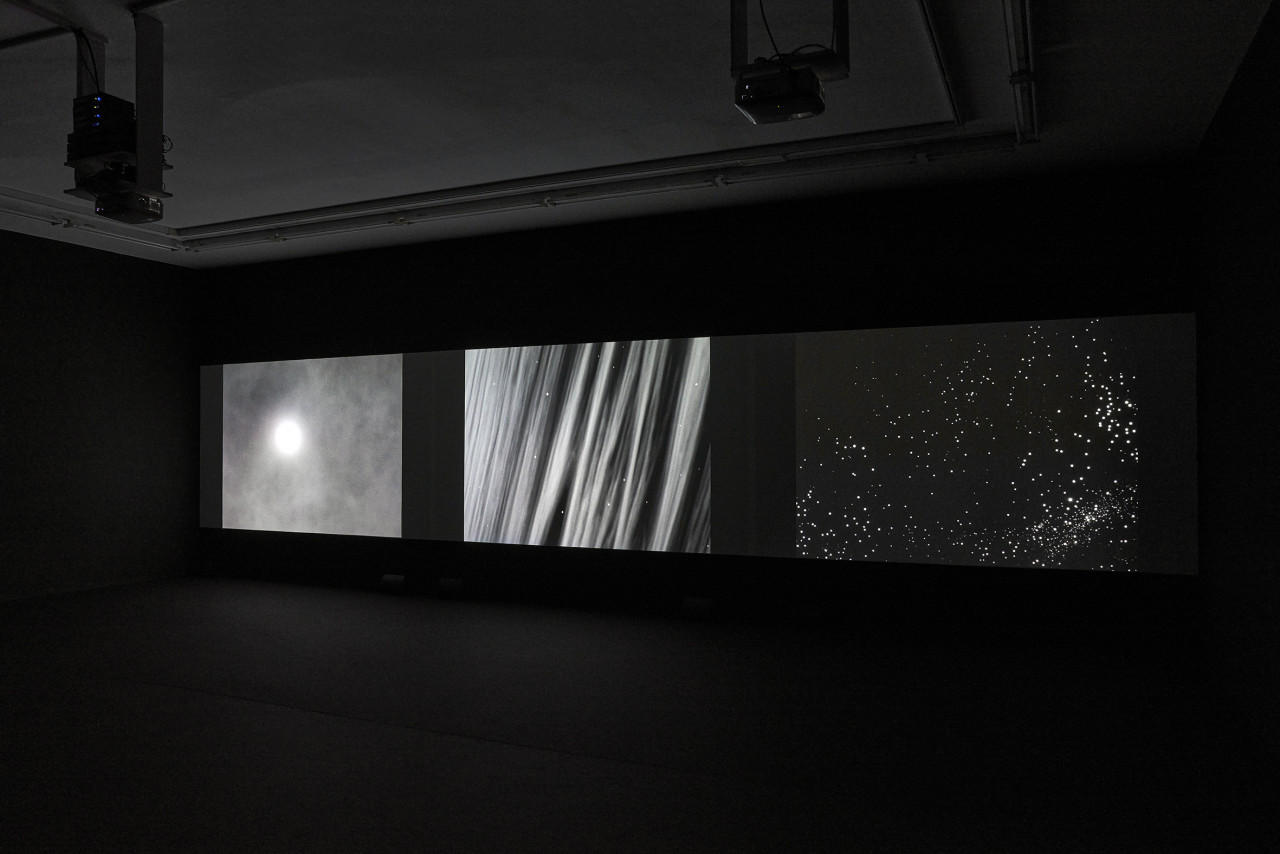

There is a trait that cinema and fire share: the imagination of movement. In that sense Pauline Julier’s films, videos and installations partake in the effort of reconnecting the moving image with the question of the fundamental constituents of the world, the “elements”– as pre-Socratic philosophy would put it. What does this mean? That a film allows us to go deep into the basic principles that constitute the material world, humans included. What are these elements? They are culturally diverse. While in the West we only name air, water, earth, fire and aether, in Eastern traditions, metal was added. Indeed, matter and how it emerges in the filmic matter is a very important element in the epistemology created by Pauline Julier. Her films, while demonstrating the need for systematization associated with all rational thought – because of its sequential narrative flow – also reveal and insist on the collapse of any system in the face of the infinite richness of experience.